Zen Buddhism: Overview of its historical and philosophical roots

Zen Buddhism is frequently portrayed in modern popular culture as a set of cryptic sayings, minimalist aesthetics, and serene meditation gardens. However, these representations often isolate Zen from its deeper philosophical and historical foundations. Contrary to such portrayals, Zen is not an isolated or esoteric tradition detached from Buddhist roots. Rather, it is a school within Mahāyāna Buddhism, one that emphasizes direct experiential realization of the foundational teachings first articulated by Siddhartha Gautama and later refined in Mahāyāna thought, particularly through the Madhyamaka and Huayan traditions.

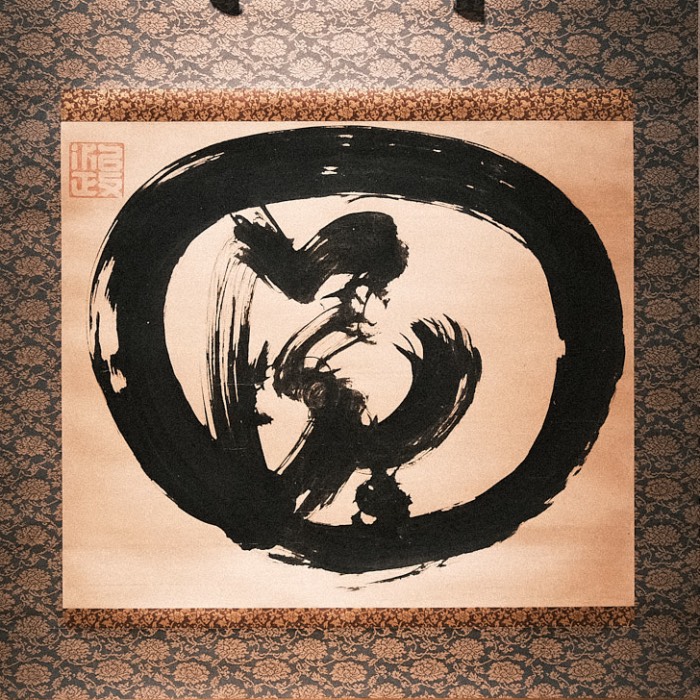

Ensō (“Zen circle”) calligraphy by Kanjuro Shibata XX, c. 2000. The ensō is a symbol of enlightenment, the universe, and the void in Zen Buddhism. It represents the moment when the mind is free to let the body create. The circle is often left open to symbolize the imperfection of life and the beauty of incompleteness. The act of drawing the circle is a form of meditation in itself, embodying the Zen principle of “just doing” without attachment to outcome. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0; modified).

This post marks the beginning of a new series exploring Zen Buddhism as a tradition deeply rooted in classical and Mahāyāna Buddhist thought. The first post in this series offers a contextual and philosophical overview of Zen Buddhism as a historically continuous development within the broader framework of Buddhist philosophy. It focuses on Zen’s unique interpretative lens, its roots in early Indian thought, and its evolution through Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese cultures.

Note on terminology

In literature, the term Chán (禪, short for 禪那, Pinyin: chánnà) typically refers to the development of this tradition in China, while Zen is used for its evolution in Japan. However, for the purposes of this series, I will use these terms more loosely and interchangeably to refer to the broader tradition as a whole.

Zen as a continuation of core Buddhist principles

Zen, from the Chinese Chán (derived from the Sanskrit dhyāna, meaning meditation), is not a departure from Buddhism but a distinct method of expressing and realizing its essential insights. These insights include the impermanence of all things (anicca), the absence of a permanent self (anattā), and the interdependent origination of all phenomena (paṭicca-samuppāda). Zen retains these principles while framing them in a mode of practice and language that emphasizes immediacy and non-conceptual understanding, making them accessible not through theoretical argument but through direct engagement with the present moment.

While Siddhartha Gautama articulated these teachings in analytic and discursive forms appropriate to the Indian philosophical milieu of his time, Zen Buddhism developed in dialogue with Chinese cultural and intellectual traditions that valued intuitive and embodied ways of knowing. Consequently, Zen tends to avoid abstraction and instead employs metaphor, paradox, poetic gesture, and everyday action to convey the same insights. Rather than viewing this as a simplification, it represents a different epistemological approach — one that seeks realization through lived experience rather than conceptual analysis. In this sense, Zen can be seen not as rejecting early Buddhist doctrines, but as reinterpreting them through a method that privileges immediacy, spontaneity, and presence.

Philosophical foundations: Madhyamaka, Yogācāra, and Huayan

Zen Buddhism is deeply influenced by earlier Mahāyāna schools, particularly Madhyamaka and Yogācāra. The Madhyamaka school, founded by Nāgārjuna, emphasized the concept of śūnyatā (emptiness), arguing that all phenomena lack inherent existence. This was not a nihilistic claim, but a refinement of Siddhartha’s earlier teachings: by denying intrinsic essence, Madhyamaka affirmed the relational, dependent nature of reality.

Yogācāra, often considered a “mind-only” school, explored the nature of perception and consciousness, positing that what we take as external reality is shaped by mental formations. Zen absorbed both perspectives, often employing them without overt theoretical exposition. Instead, Zen points directly to the nature of mind through practice.

The Chinese Huayan school, with its doctrine of interpenetration, also played a pivotal role in shaping Zen. Fazang’s metaphor of Indra’s Net — a cosmic web in which each jewel reflects all others — encapsulates the vision of reality as an infinite interplay of interdependent phenomena. Zen appropriated this insight, grounding it in everyday experience and often expressing it through concrete activity rather than metaphysical doctrine.

Central practices: From meditation to embodied presence

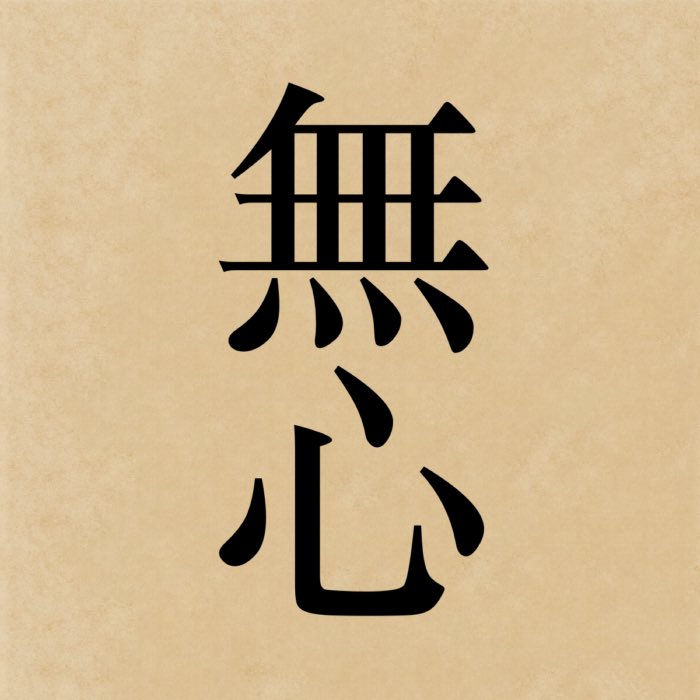

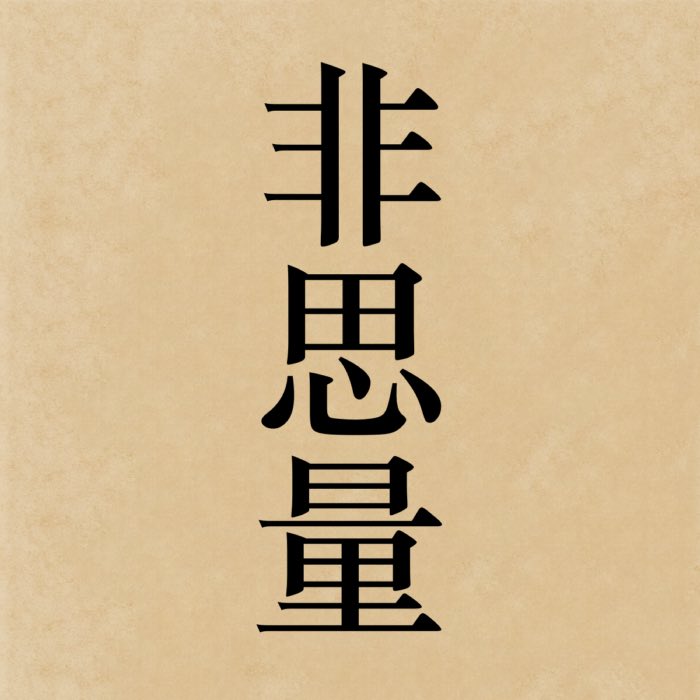

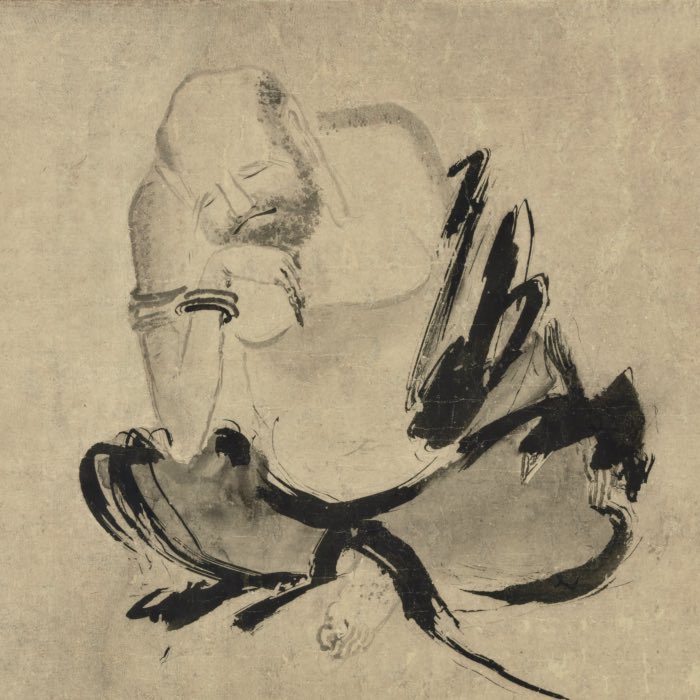

Although Zen is most often associated with seated meditation (zazen), it would be reductive to equate the entire tradition with this one practice. Zazen, especially in the form known as shikantaza (“just sitting”), is central in some Zen lineages, particularly the Japanese Sōtō school. However, this form of meditation is less about attaining specific states and more about radically attending to the present moment, without striving or goal-setting. It embodies the Mahāyāna view that enlightenment is not something to be achieved, but something to be recognized as already present.

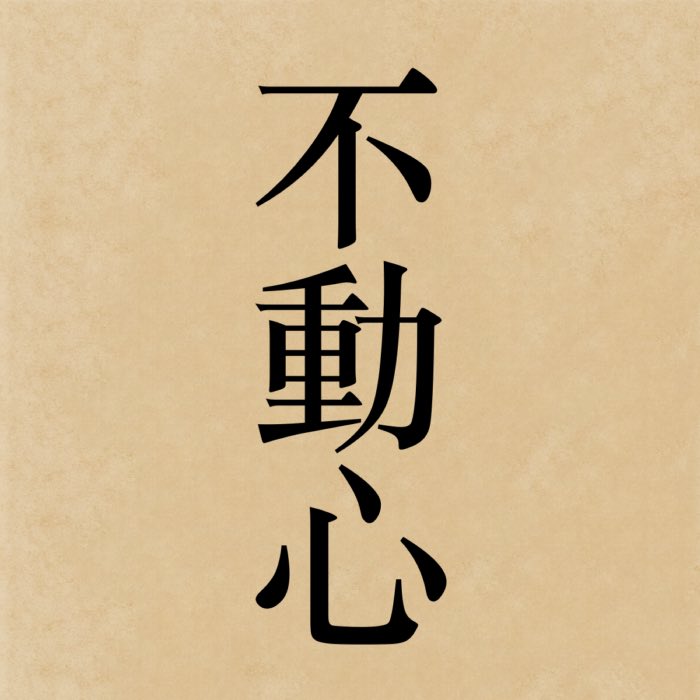

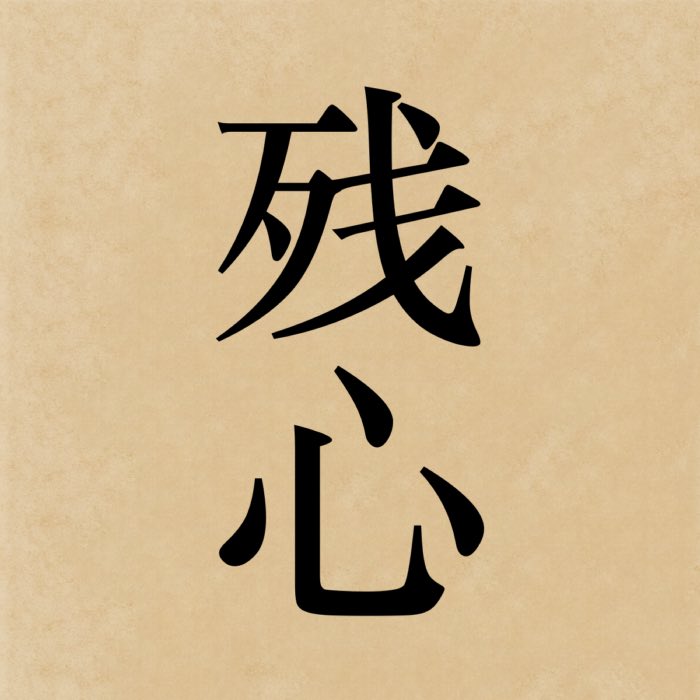

Other forms of practice include the use of kōan (paradoxical riddles or dialogues) designed to disrupt habitual patterns of thought and elicit direct insight into the nature of mind and reality. Unlike doctrinal study, which can reinforce conceptual thinking, kōan practice is meant to destabilize it, opening a space for intuitive understanding. Such experiences of direct recognition are often described in Zen as kenshō — a first glimpse into the nature of mind — and satori, a deeper or more complete awakening. These are not regarded as final goals but as shifts in perception that illuminate the impermanence and interdependence underlying all phenomena.

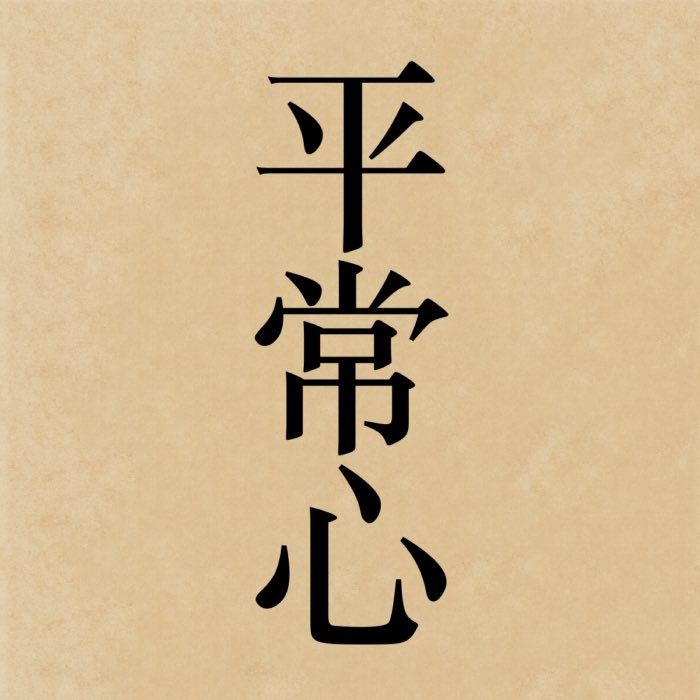

Zen also emphasizes mindfulness in daily life, turning ordinary actions — such as sweeping, eating, or walking — into opportunities for awakening. This approach aligns with its rejection of dualism between the sacred and the mundane. The same attentiveness cultivated in meditation is extended into all aspects of life.

Zen’s diverse methods — from shikantaza and zazen to the sudden flashes of insight (kenshō or satori) — are not isolated rituals but interwoven expressions of a single aim: the direct realization of suchness (tathatā), the way things truly are beyond conceptual distinctions. The practice of sitting without striving, encountering a kōan without resolving it intellectually, or attending fully to the act of sweeping a floor — all are intended to dissolve the illusion of separation between self and world, subject and object. In this way, Zen embodies the Mahāyāna insight that awakening is not a distant goal but an ever-present possibility already immanent in every moment of ordinary life. Its emphasis on immediacy and non-duality affirms that the “Buddha-nature” is not something to be acquired, but something obscured — and to see it is simply to stop turning away.

Historical development: From India to East Asia

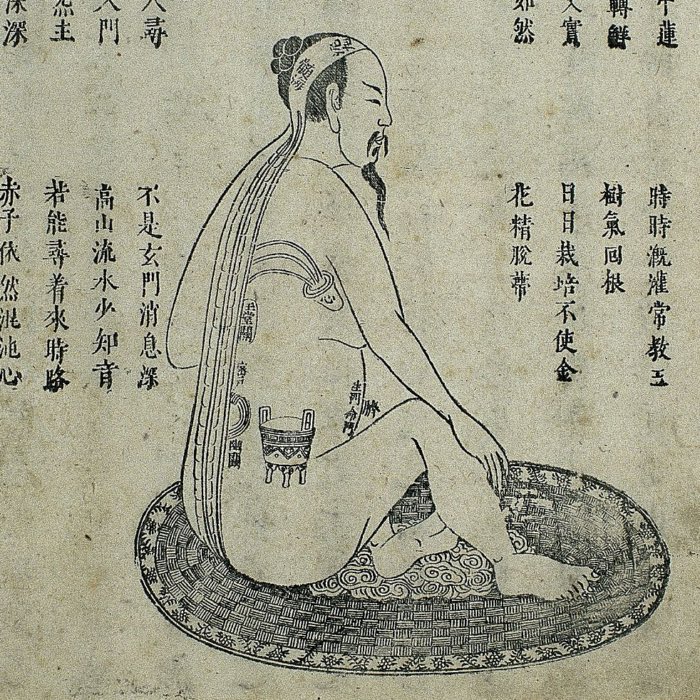

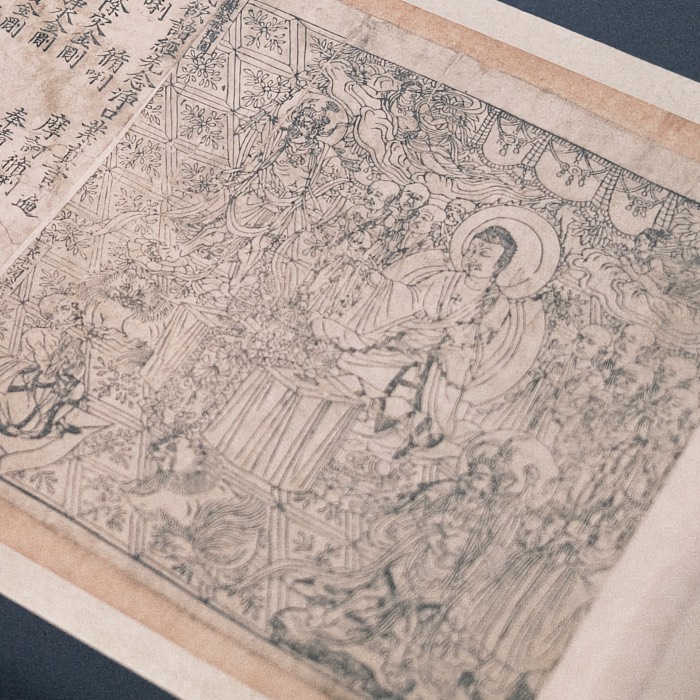

Zen’s historical trajectory begins with the early transmission of Indian Buddhist teachings into China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), around the 1st to 2nd centuries CE. These transmissions included both doctrinal texts and meditative practices, brought by itinerant monks such as An Shigao and Lokakṣema, who translated important works into Chinese and laid the foundations for what would later become various Chinese Buddhist schools.

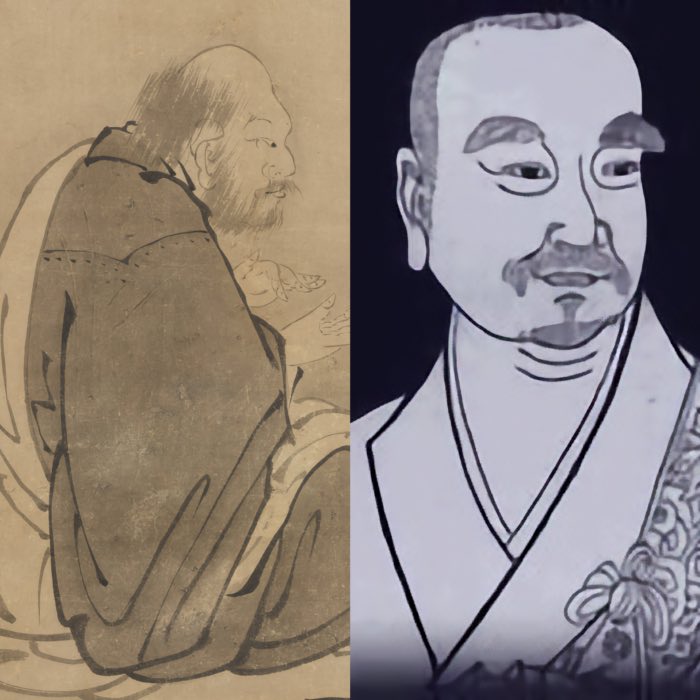

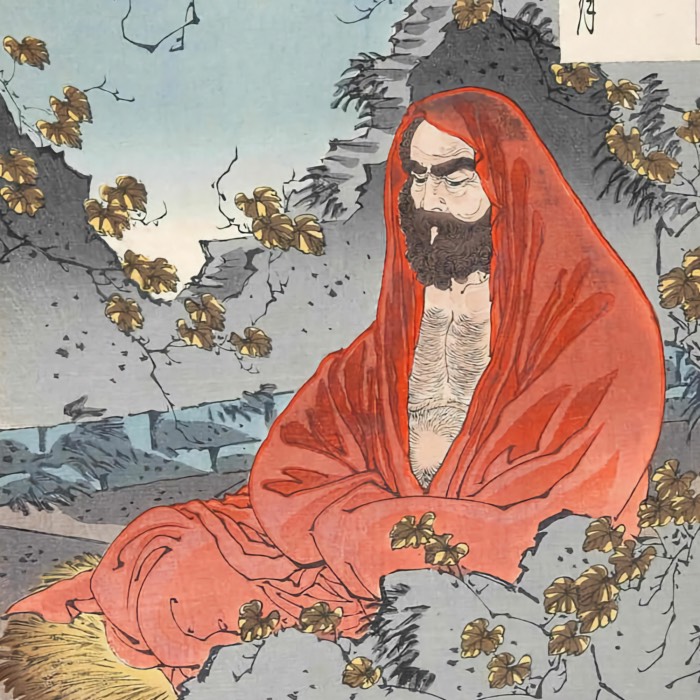

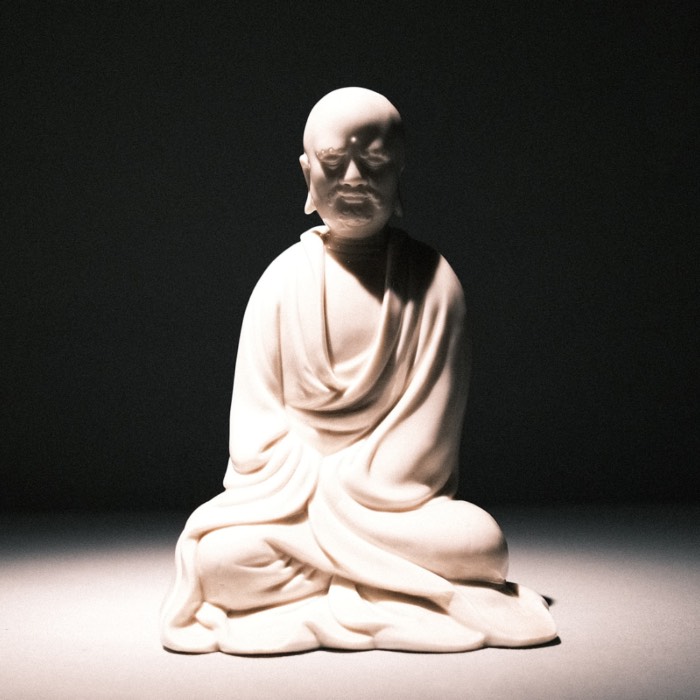

By the 5th and 6th centuries CE, Buddhist practices in China began to integrate more deeply with Daoist ideas, particularly those emphasizing naturalness and spontaneity. It was in this cultural and philosophical context that the legendary figure of Bodhidharma, traditionally dated to the early 6th century, is said to have arrived in China. He is credited with emphasizing seated meditation and a transmission of the Dharma “outside the scriptures.” While historical verification of Bodhidharma’s life is limited, the ideas associated with him reflect a clear shift toward meditative immediacy, direct experience, and a critique of overly scholastic or ritualistic approaches to the Dharma. His attributed teachings laid the groundwork for what would become Chán in China and later Zen in Japan.

The development of Zen continued through a series of key figures often referred to as patriarchs, culminating in a division between the Northern and Southern schools in the Tang dynasty. The latter, emphasizing sudden awakening, became dominant and shaped the trajectory of Zen into its classical form.

Zen Buddhism also took root beyond China and Japan. In Korea, the Seon tradition emerged, formally established during the Unified Silla period in the late 8th century. It was profoundly shaped by Chinese Chán and integrated with indigenous Korean practices. Figures such as Jinul (1158–1210) played a central role in systematizing Korean Seon, emphasizing a synthesis of meditation and doctrinal study. In Vietnam, Thiền Buddhism developed from similar roots in Chinese Chán. Introduced as early as the 6th century, Thiền evolved through multiple lineages, blending with local culture and later Confucian and Daoist thought. Both Seon and Thiền continue to be vital expressions of Zen practice in East Asia today.

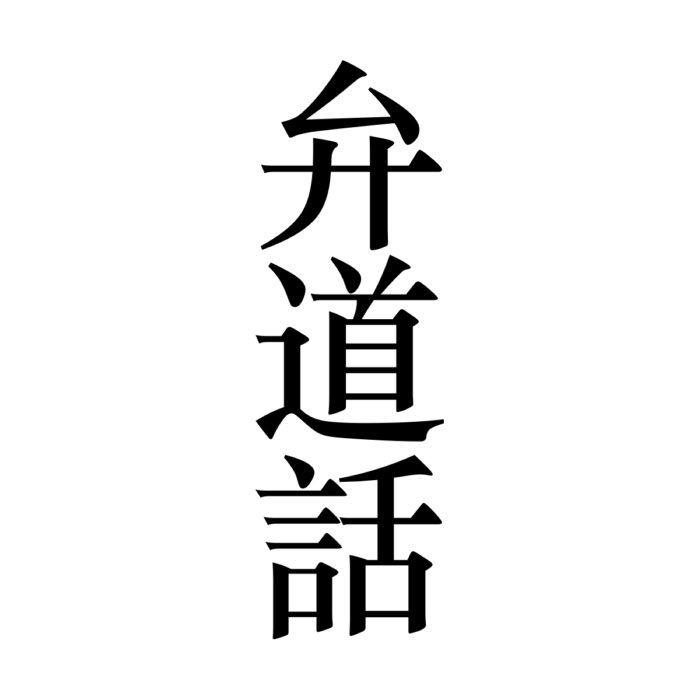

In Japan, Zen underwent further transformations, most notably through the work of Dōgen Zenji in the 13th century. Dōgen emphasized the identity of practice and realization, famously stating that “practice is enlightenment.” His writings, especially Shōbōgenzō and Bendōwa, deeply influenced Japanese Sōtō Zen and further cemented Zen’s integration into everyday life.

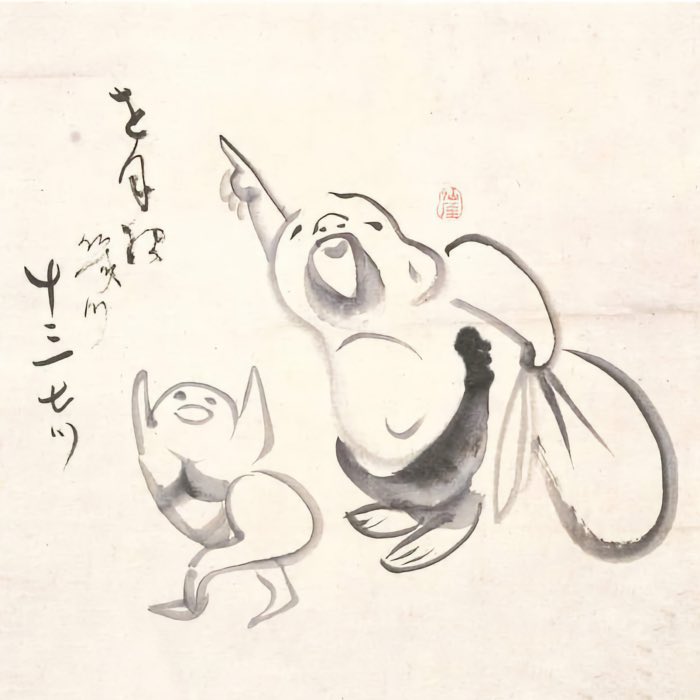

Another major school to emerge was the Rinzai school (Linji zong in Chinese), named after the Tang dynasty master Linji Yixuan (d. ca. 866). Known for his abrupt methods, shouting, and unconventional teaching strategies, Linji emphasized sudden awakening and direct insight, often catalyzed through kōan practice. The Rinzai tradition became especially influential in Japan from the Kamakura period onward, shaping not only monastic practice but also artistic and warrior culture. While distinct in method from Dōgen’s Sōtō Zen, the Rinzai school shares the same foundational goal of awakening to one’s inherent Buddha-nature.

Expression through art, language, and culture

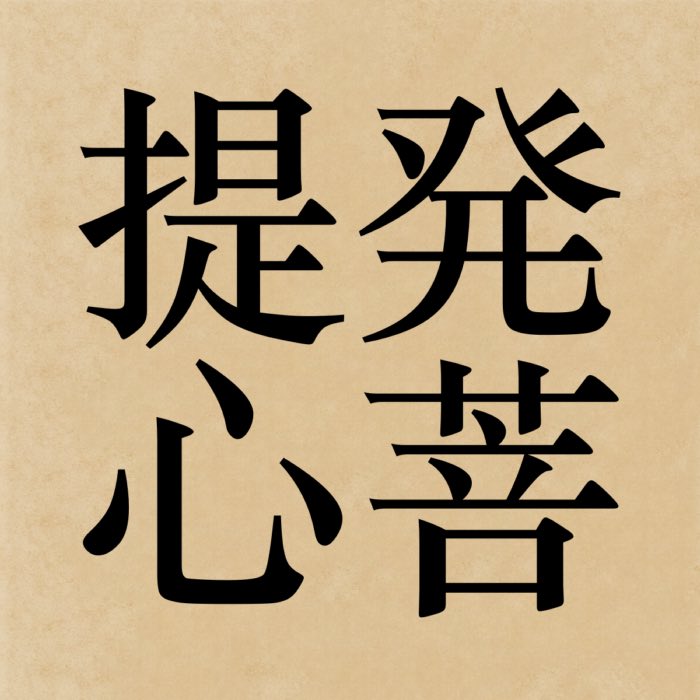

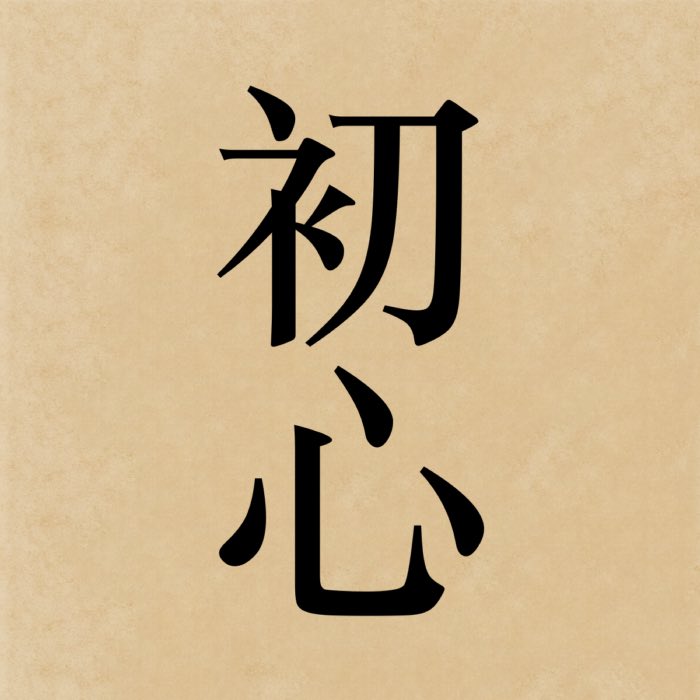

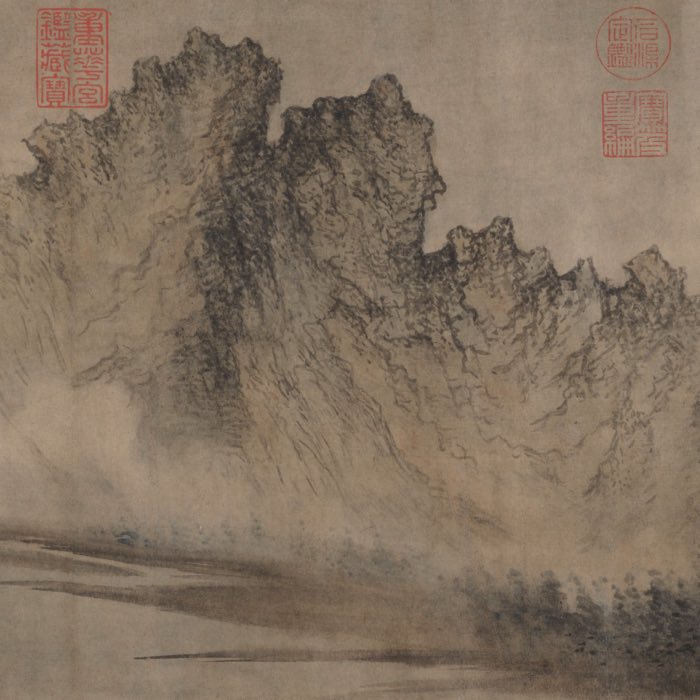

One of the distinguishing features of Zen Buddhism is its unique mode of expression. Rather than articulating philosophy in abstract terms, Zen prefers gesture, poetry, and even silence. A raised finger, a single word, or a bowl of tea can serve as a complete teaching. This minimalism is not an evasion of doctrine but a deliberate strategy to point beyond conceptual structures, aiming instead at a direct, intuitive apprehension of reality.

Zen aesthetics, evident in practices such as calligraphy, garden design, and the tea ceremony, reflect its emphasis on simplicity, impermanence, and the beauty of the present moment. The sparse elegance of these forms embodies the Zen attitude toward transience and mindfulness, where form itself becomes a vehicle of insight. These cultural expressions are not peripheral but are themselves understood as vehicles of realization, inviting the observer or participant to enter a state of attentiveness and clarity akin to that cultivated in meditation.

Doctrinal core without doctrinal clutter

Despite its deliberate avoidance of technical scholasticism, Zen embodies the central tenets of classical Buddhism in full. The denial of an enduring self (anattā), the recognition of constant impermanence (anicca), and the understanding that suffering (dukkha) arises from clinging to what is unstable and illusory remain foundational. Zen’s distinctiveness lies in its method of expression: it does not elaborate these truths through doctrinal exposition but points directly to them through lived, immediate experience. Rather than offering philosophical arguments, Zen confronts practitioners with the raw texture of reality, encouraging an awakening that bypasses conceptual elaboration altogether.

In this sense, Zen reaffirms and radicalizes the Mahāyāna emphasis on prajñā (wisdom) and karuṇā (compassion) by grounding them not in metaphysical claims, but in the practice of attentiveness and ethical presence. While it lacks the elaborate ethical codes found in other Buddhist traditions, Zen demands rigorous self-awareness and responsiveness to others as intrinsic aspects of awakening. The teacher-student transmission, central to Zen lineages, is not a ritual of authority but a moment of insight — directly pointing to the nature of mind. The authority of the tradition rests not in scriptures or institutions, but in the awakening it enables, repeated anew in every generation.

Conclusion

Zen Buddhism is neither a mystical offshoot nor a radical departure from classical Buddhist thought. Rather, it is a deeply rooted development within the Mahāyāna tradition, distinguished by its direct, non-conceptual approach to the same core insights articulated by Siddhartha Gautama and refined through the philosophical systems of Madhyamaka, Yogācāra, and Huayan. By emphasizing impermanence, non-self, and interdependent origination, Zen seeks not doctrinal certainty but experiential realization — a form of insight grounded in lived immediacy. While this emphasis on direct experience is present in other Buddhist traditions, such as aspects of Vajrayāna or Theravāda meditation, Zen distinguishes itself by centering this immediacy as the primary vehicle of awakening and by stripping away many of the doctrinal, ritual, and institutional layers that can accompany other paths. In doing so, it articulates a uniquely pared-down approach that has both radical and conservative dimensions: radical in its rejection of conceptual elaboration, conservative in its return to the immediacy of practice as the heart of the path.

Historically, Zen emerged through a transregional transmission of ideas and practices, shaped by Chinese culture and later expressed in distinct Korean, Vietnamese, and Japanese forms. This evolution was never a break from Buddhist principles but rather a transformation in their mode of access. Zen’s characteristic methods — from shikantaza and kōan practice to its cultural expressions in art and everyday life — reveal an ongoing attempt to bring philosophy into direct contact with action and perception.

Zen presents both a challenge and a contribution to the broader Buddhist tradition. It challenges traditions that emphasize textual study, ritual formalism, or metaphysical speculation by calling for an immediacy that is difficult to institutionalize. Yet, it also contributes a method of practice that is deeply rigorous, psychologically refined, and compatible with everyday life. Its refusal to rely on fixed forms makes it harder to systematize, but also more resilient and adaptable.

In the context of modern society, Zen offers potential value not by promising spiritual escape or metaphysical truths, but by fostering attention, clarity, and ethical responsiveness in the here and now. The human mind, when left on its own and kept untrained, is marked by distraction, fragmentation, and the tendency to become entangled in abstractions Zen’s insistence on presence, simplicity, and the non-duality of thought and action may serve as a corrective. It encourages not withdrawal from the world, but deeper engagement with its unfolding reality — one breath, one gesture, one moment at a time.

In this light, Zen should not be viewed as a separate or alternative path beside Buddhism, but as a deeply integrated expression of it. Its emphasis on direct realization through practice aligns fully with the Noble Eightfold Path (magga) outlined in the Fourth Noble Truth: a path of ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom. Zen’s aim is the same as that of all Buddhist schools — to end suffering by cutting through delusion and seeing reality as it truly is. What distinguishes Zen is not its destination, but its method: a radical trust in the immediacy of experience, a refusal to conceptualize the ineffable, and a commitment to live insight rather than merely understand it. In doing so, Zen exemplifies a living Dharma, one that is both ancient in its roots and perpetually renewed in each act of attentiveness.

References and further reading

- Oliver Bottini, Das große O.-W.-Barth-Buch des Zen, 2002, Barth im Scherz-Verl, ISBN: 9783502611042

- Heinrich Dumoulin, Geschichte des Zen-Buddhismus, Band 1+2, 2019, 2., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage, Francke A. Verlag, ISBN: 9783772085161

- Hans-Günter Wagner, Buddhismus in China: Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart, 2020, Matthes & Seitz Berlin, ISBN: 978-3957578440

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

comments