Three vehicles, three schools: How Buddhist teachings evolved and spread

Buddhism, as it spread across Asia, gave rise to both diverse philosophical interpretations and distinct institutional forms. To understand this development, it is helpful to distinguish between two perspectives. The first is the doctrinal metaphor of the ‘vehicles’ (yāna), a way of describing different approaches or levels of teaching aimed at different capacities of practitioners. This concept was especially developed within Mahāyāna literature to frame earlier and concurrent paths as the small (hīnayāna), great (mahāyāna), and ultimately one (ekayāna) vehicle. The second perspective focuses on the historical schools of Buddhism — Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna — each of which developed in specific regions, languages, and cultural contexts. These schools are often associated with different texts, practices, and institutions, but they do not always align neatly with the doctrinal metaphor of the three vehicles. Understanding both frameworks helps us see how Buddhism adapted and evolved across time without reducing its complexity to a single narrative.

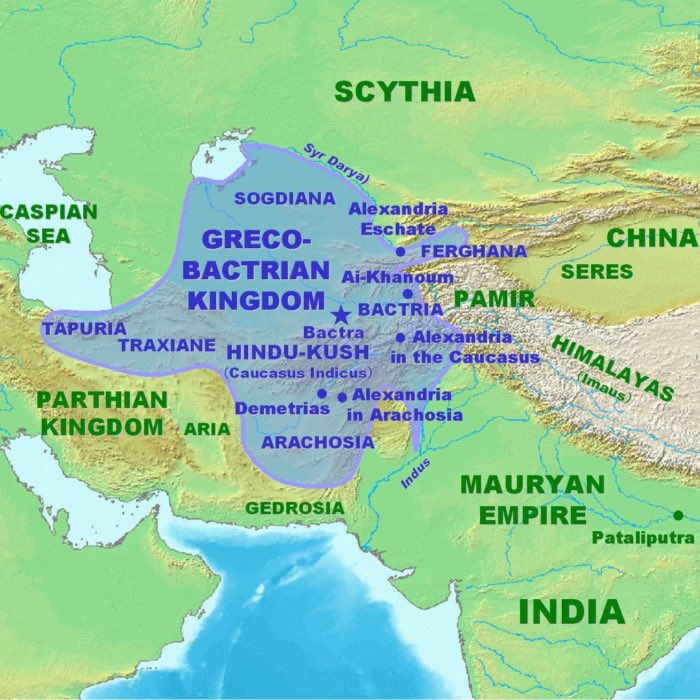

Buddhist expansion in Asia: Originating from India, Buddhism spread to Central Asia, China, Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia. The map shows the routes of transmission and the regions where Buddhism took root. The spread of Buddhism was facilitated by trade routes, cultural exchanges, and the patronage of local rulers. For instance, Mahayana Buddhism first entered the Han Dynasty China through the Silk Road during the Kushan Era. The overland and maritime “Silk Roads” were interlinked and complementary, forming what scholars have called the “great circle of Buddhism”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Buddhist expansion in Asia: Originating from India, Buddhism spread to Central Asia, China, Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia. The map shows the routes of transmission and the regions where Buddhism took root. The spread of Buddhism was facilitated by trade routes, cultural exchanges, and the patronage of local rulers. For instance, Mahayana Buddhism first entered the Han Dynasty China through the Silk Road during the Kushan Era. The overland and maritime “Silk Roads” were interlinked and complementary, forming what scholars have called the “great circle of Buddhism”. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0)

The concept of yāna (vehicle)

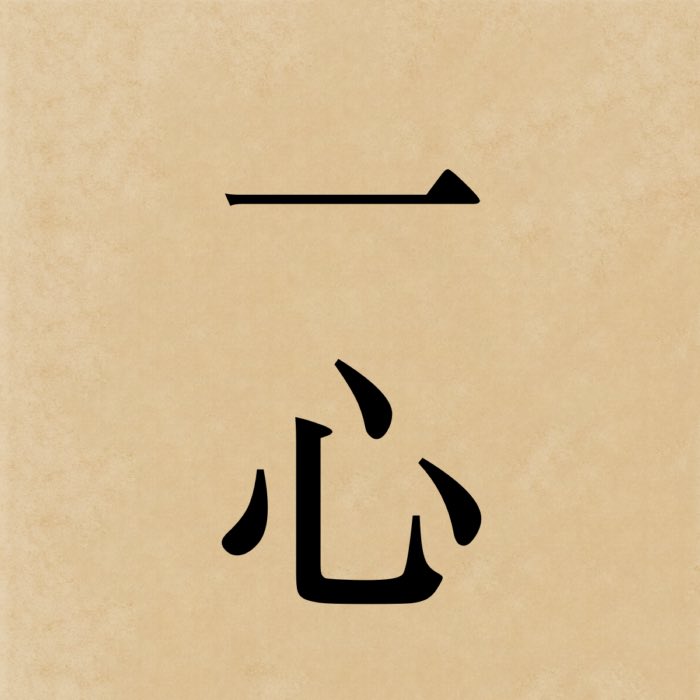

The Sanskrit word yāna, meaning “vehicle” or “conveyance,” began as a metaphor in early Indian religious contexts to describe a path or method that carries one toward liberation. In early Buddhist usage, it was simply one of many metaphors for practice, without any strong doctrinal emphasis. However, as Buddhist teachings diversified and evolved, especially within Mahāyāna traditions, the term became central in categorizing and evaluating different spiritual paths.

The notion of multiple vehicles emerged in Mahāyāna texts around the first few centuries CE. These texts often referred to three principal paths: the hīnayāna (“small vehicle”), associated with individual liberation (primarily referring to śrāvakas and pratyekabuddhas); the mahāyāna (“great vehicle”), aimed at universal liberation through the Bodhisattva path; and the ekayāna (“one vehicle”), presented as the ultimate synthesis in certain sūtras like the Lotus Sūtra, where all valid paths are revealed to lead toward buddhahood.

The term hīnayāna is problematic and generally avoided in modern scholarship and inter-sectarian dialogue. It was a polemical label used by Mahāyāna authors to contrast their vision of universal salvation with what they saw as narrower goals. No school ever self-identified as hīnayāna, and today, the term is seen as derogatory. Instead, historians and practitioners refer more neutrally to early Buddhism or to specific schools like Theravāda, which is the only surviving form of early non-Mahāyāna tradition.

Historical development of Buddhist schools

The historical development of Buddhist schools can be understood through the lens of the three major traditions: Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna. Each of these schools has its own unique characteristics, texts, and practices, shaped by the cultural and historical contexts in which they developed.

The early Buddhist community and the first schisms

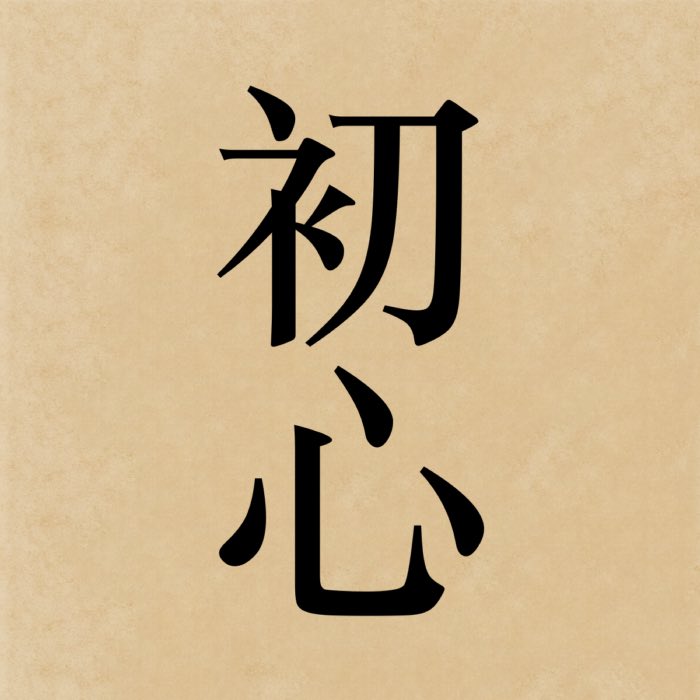

After the death of Siddhartha Gautama, the early Buddhist community was characterized by a relatively unified set of teachings and practices, maintained through oral transmission and communal recitation. The monastic order (saṅgha) played a central role in preserving the Dharma, and the first few centuries saw efforts to standardize both doctrine and monastic discipline.

Over time, as Buddhism spread geographically and interacted with varying cultural contexts, differing interpretations of doctrine and practice began to surface. These differences culminated in what is traditionally known as the first major schism, which likely took place around the 4th century BCE. The division resulted in the formation of two major factions: the Sthavira (Elders), who emphasized stricter adherence to established rules, and the Mahāsāṃghika (Great Community), who advocated a more flexible approach to monastic discipline and were possibly more open to doctrinal innovation.

This early schism was not necessarily the result of a dramatic rupture, but rather part of a gradual diversification of viewpoints within an expanding and increasingly complex religious community. While later sources often portray the split in stark terms, modern scholarship suggests that the process was more evolutionary than revolutionary. Nonetheless, this division set the stage for further developments in Buddhist thought and laid the groundwork for the emergence of various early schools (nikāyas), some of which contributed to later traditions like Theravāda and Mahāyāna.

Theravāda as the surviving form of early Buddhism

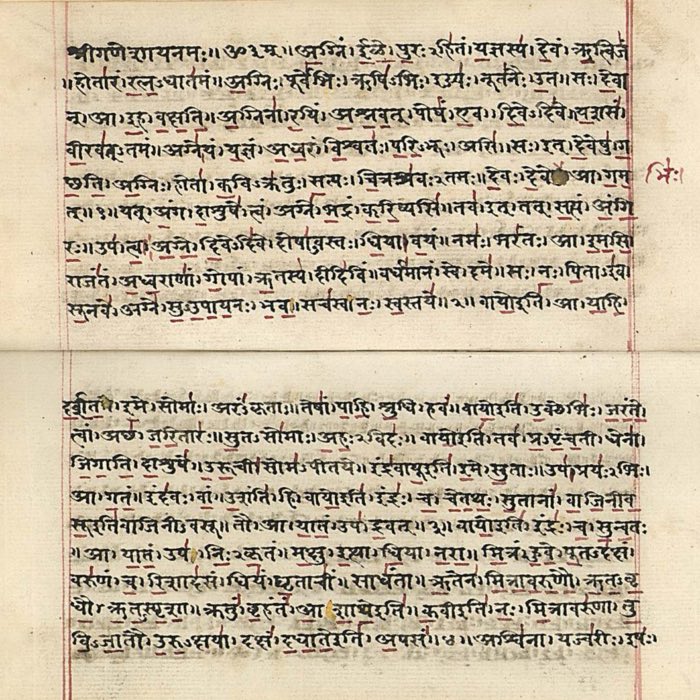

Theravāda, meaning “Teaching of the Elders,” is the only surviving school from the early Buddhist tradition and is most directly linked to the Sthavira lineage, one of the earliest divisions that occurred in the Buddhist community after the death of Siddhartha Gautama. It preserves the most complete and cohesive body of texts from early Buddhism, known collectively as the Tipiṭaka (“Three Baskets”) or Pāli Canon, written in the Pāli language. This canon includes the Vinaya Piṭaka (rules of monastic discipline), the Sutta Piṭaka (discourses of the Buddha), and the Abhidhamma Piṭaka (philosophical and psychological analysis).

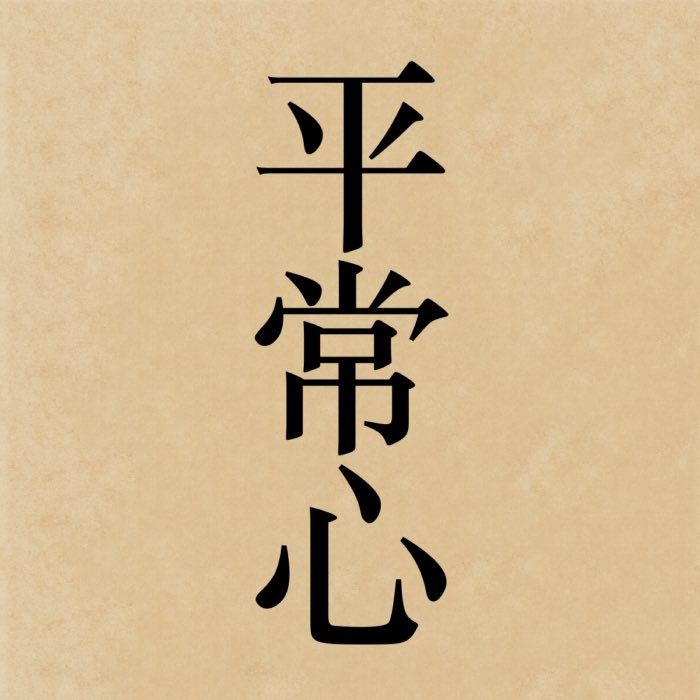

Theravāda doctrine centers on the ideal of the arahant — a person who has achieved liberation from the cycle of rebirth (saṃsāra) by following the Eightfold Path. It teaches that liberation comes through a gradual training rooted in the cultivation of ethical conduct (sīla), mental discipline through meditation (samādhi), and insight into the nature of reality (paññā). Central to this path is the experiential understanding of impermanence (anicca), non-self (anattā), and suffering (dukkha).

While often considered more conservative than Mahāyāna traditions, Theravāda contains a rich variety of interpretive traditions and contemplative methods. Its meditation schools, particularly those rooted in Burmese Vipassanā and Thai forest monasticism, have gained international prominence. Despite its adherence to early scriptures, Theravāda has also shown considerable adaptability over time, incorporating ritual, devotion, and scholastic commentary in different regional contexts.

Today, Theravāda is practiced predominantly in Sri Lanka, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. In these countries, it is closely integrated with cultural, national, and social institutions. Beyond Asia, Theravāda has grown through global interest in meditation and mindfulness, and through diaspora communities. As such, it serves both as a living tradition and as an important resource for scholars and practitioners seeking insight into the foundational layers of Buddhist thought and practice.

Mahāyāna as a broad movement, not a single school

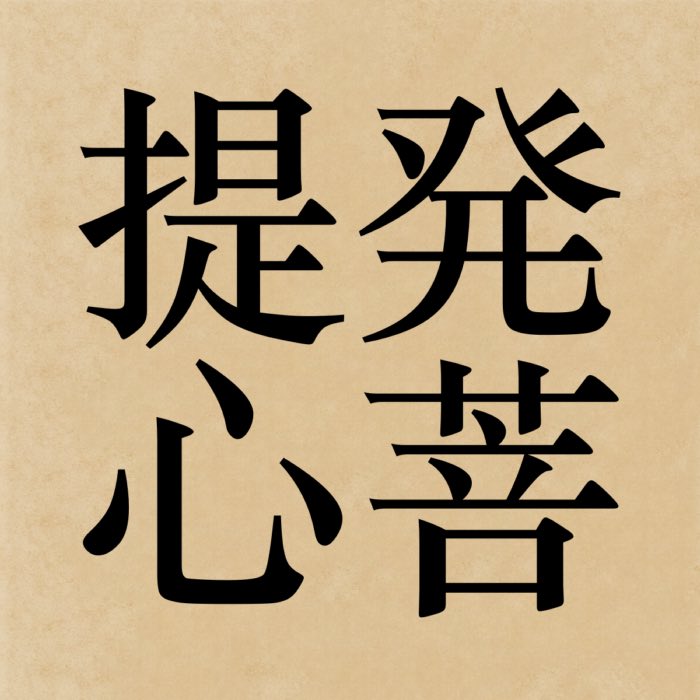

Mahāyāna, or “Great Vehicle”, emerged around the 1st century CE in India as a dynamic and reformative movement within the broader Buddhist tradition. It positioned itself as a more expansive and compassionate path, oriented toward the enlightenment of all sentient beings, rather than individual liberation alone. At the heart of Mahāyāna is the Bodhisattva ideal: a practitioner vows to attain full Buddhahood in order to help liberate others, embodying deep compassion (karuṇā) and wisdom (prajñā).

Unlike Theravāda, Mahāyāna is not a single, unified school but a pluralistic and evolving framework encompassing a variety of doctrines, texts, and practices. Its emergence was marked by the appearance of new scriptural texts — Mahāyāna sūtras — which were often composed in Sanskrit and preserved in Chinese and Tibetan translations. Among the earliest and most influential of these are the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras (“Perfection of wisdom”), which teach the doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā), the absence of inherent existence in all phenomena. These texts introduced a radical reinterpretation of core Buddhist principles and formed the foundation for subsequent philosophical systems.

Two major philosophical schools emerged from this milieu. The Madhyamaka school, founded by Nāgārjuna, articulated a rigorous analysis of emptiness and dependent origination, aiming to deconstruct all fixed views and avoid extremes of nihilism or essentialism. The Yogācāra school, often called “Mind-Only”, emphasized the constructive role of consciousness and perception, proposing that what we experience is shaped by deep cognitive patterns and karmic imprints.

Mahāyāna also expanded the cosmological and devotional dimensions of Buddhism, introducing celestial Buddhas and Bodhisattvas like Amitābha, Avalokiteśvara, and Mañjuśrī. Devotional practices such as chanting, visualization, and ritual offerings were often directed toward these figures. Central to many Mahāyāna schools is the vision of multiple paths suited to the varied capacities of beings — a concept consistent with the idea of “skillful means” (upāya-kauśalya).

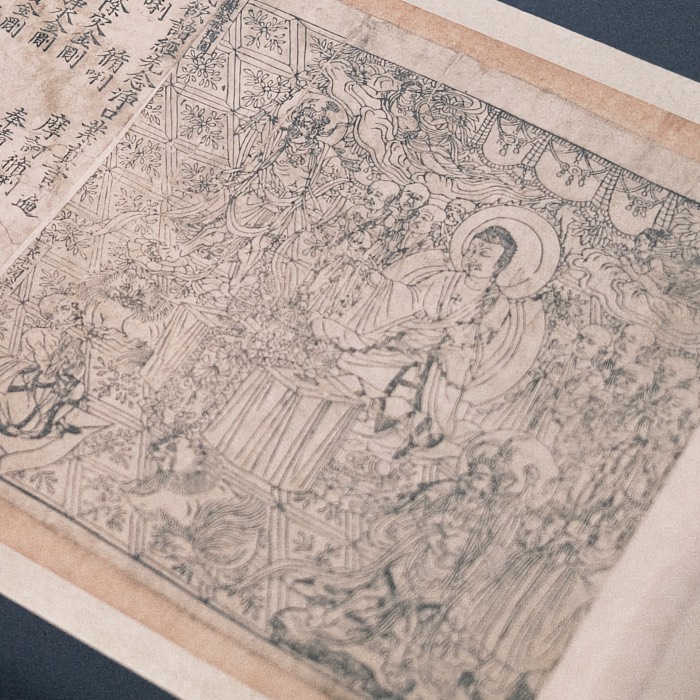

Geographically, Mahāyāna spread widely across Central and East Asia, where it took root in culturally distinct forms. In China, it gave rise to influential schools such as Tiantai, Huayan, Pure Land, and Chán (Zen). These schools were further transmitted to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, each developing unique interpretations while maintaining core Mahāyāna themes.

In modern times, Mahāyāna continues to be a vital force within global Buddhism. Its emphasis on compassion, emptiness, interdependence, and the aspiration to save all beings makes it both a philosophical and a spiritual path that resonates across cultures. As a living tradition, it continues to evolve while drawing on its rich doctrinal and devotional heritage.

Vajrayāna as a tantric development within Mahāyāna

Vajrayāna, often translated as the “Diamond Vehicle” or “Thunderbolt Vehicle,” is a form of Buddhism that evolved from within the Mahāyāna tradition but distinguishes itself through its esoteric, ritualistic, and often highly symbolic practices. It emerged in India between the 6th and 8th centuries CE, at a time of great philosophical and religious ferment, and was shaped by interactions between Mahāyāna Buddhism, Hindu Śaiva tantra, and indigenous yogic traditions.

At its core, Vajrayāna seeks to accelerate the path to enlightenment by engaging not just the mind, but the body and speech, in a transformative process. It utilizes methods such as mantra (sacred syllables), mudrā (ritual gestures), mandala (sacred diagrams), and deity visualization to reframe perception and cut through dualistic thinking. These practices are based on an extensive body of texts known as the tantras, which are often transmitted through oral instruction and require initiation (abhiṣeka) by a qualified teacher. The practitioner works closely with a spiritual guide or guru, who is seen as embodying the awakened state and whose role is essential to the transformative process.

Philosophically, Vajrayāna is rooted in Mahāyāna principles — especially the doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā) and the Bodhisattva vow — but it adds a distinctive emphasis on harnessing the very elements of samsāric existence (desire, aversion, ignorance) as fuel for awakening. This bold strategy is known as the path of transformation rather than renunciation. Vajrayāna views all phenomena as inherently pure and luminous when rightly understood, a perspective expressed in the concept of sahaja (spontaneous presence) and the union of bliss and emptiness.

Vajrayāna flourished most prominently in Tibet, where it became the dominant tradition and formed the basis for what is often called Tibetan Buddhism. Here, it was systematized into four major schools: Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug, each with unique lineages and emphases. Vajrayāna also took root in Mongolia, Bhutan, Nepal, and parts of China and Japan, where it influenced traditions like Shingon Buddhism.

Beyond its ritual and doctrinal sophistication, Vajrayāna developed rich artistic, meditative, and ethical cultures. Its temples are adorned with elaborate thangka paintings and mandalas, and its literature includes not only tantras but commentaries, philosophical treatises, and spiritual biographies (namthar). Despite its esoteric nature, Vajrayāna has attracted global interest in recent decades due to the international visibility of Tibetan teachers and the growing appeal of its integrated approach to mind and body in spiritual practice.

Today, Vajrayāna is both a living religious tradition and a profound philosophical system. It stands as a distinctive form of Buddhism that challenges conventional dichotomies — sacred and mundane, desire and renunciation, form and emptiness — by presenting a radical, holistic path to awakening.

How the “three schools” do or don’t correspond to the “three vehicles”

While the terms Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna are often thought to correspond directly with the three vehicles (hīnayāna, mahāyāna, vajrayāna), this mapping is imprecise and historically problematic. Theravāda never identified with the label hīnayāna — a term coined within Mahāyāna polemics — and in fact preserves a rich and distinct early Buddhist tradition rooted in the ancient Sthavira lineage. Its textual and doctrinal foundations predate the development of the vehicle metaphor itself, which only became prominent with the emergence of Mahāyāna literature.

Mahāyāna, by contrast, functions both as a doctrinal category — the ‘great vehicle’ promoting the Bodhisattva path — and as a broad umbrella encompassing multiple diverse schools across Asia. It includes a variety of philosophical systems, sūtric traditions, and devotional practices, making it far too heterogeneous to be reduced to a single definition or school.

Vajrayāna, while often called the ‘third vehicle,’ is better understood as a specific esoteric and ritualistic development within Mahāyāna. Its tantras, deities, and transformative yogic methods are grounded in Mahāyāna philosophy, particularly the concept of emptiness and the Bodhisattva ideal. Thus, Vajrayāna is not a separate lineage in doctrinal terms, but an advanced form of Mahāyāna practice with its own distinctive methods.

Taken together, the doctrinal metaphor of the three vehicles and the institutional division into schools like Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna illuminate different aspects of Buddhist history. The former is primarily conceptual and theological, aimed at expressing differing pedagogical and soteriological strategies. The latter reflects historical, cultural, and linguistic developments across regions. Understanding both perspectives side by side allows for a deeper appreciation of Buddhism’s complexity and adaptability.

Intersections and misconceptions

One of the most persistent misconceptions in the study and popular understanding of Buddhism is the tendency to conflate doctrinal categories (such as the ‘three vehicles’) with cultural or regional expressions (such as the ‘three schools’). This has led to oversimplifications like equating all East Asian Buddhism with Mahāyāna, or reducing Theravāda to the problematic label ‘hīnayāna.’

Why Mahāyāna isn’t all East Asian Buddhism and Theravāda isn’t Hīnayāna

Although Mahāyāna teachings and texts became dominant in East Asia, East Asian Buddhism is not monolithic. Within countries like China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, there exists a wide variety of schools that interpret Mahāyāna principles in distinct ways. For instance, Zen (Chán), Pure Land, and Tiantai are all Mahāyāna traditions, but they differ widely in practice and emphasis. Furthermore, East Asian Buddhism often integrates pre-Buddhist cultural elements and local philosophies like Confucianism and Daoism. Thus, Mahāyāna serves as a doctrinal umbrella, not a regional identity.

Similarly, equating Theravāda with the term hīnayāna is both historically inaccurate and derogatory. The term hīnayāna was coined within Mahāyāna literature to describe early Buddhist paths in contrast to the Bodhisattva ideal. However, no tradition ever self-identified as hīnayāna, and modern Theravāda practitioners strongly reject this label. Theravāda maintains its own rich, independent heritage and is not a subset of Mahāyāna, nor should it be seen as philosophically inferior.

How some schools incorporate more than one “vehicle” in practice

In reality, many Buddhist schools and practitioners do not operate strictly within the boundaries of a single vehicle. Tibetan Buddhism (Vajrayāna) explicitly includes Mahāyāna foundations and often incorporates elements from early Buddhist teachings. Monastic discipline in Tibetan schools, for example, is based on the Vinaya traditions that also underpin Theravāda.

In East Asia, Pure Land Buddhism often incorporates meditative practices associated with Chán (Zen), and some Zen masters refer to concepts from both Yogācāra and Madhyamaka philosophies. Even within Theravāda, modern movements have adopted techniques and philosophical interpretations that resonate with Mahāyāna thought, especially through global dialogues and the shared focus on meditation and compassion.

These hybrid approaches show that in practice, Buddhist traditions are fluid and responsive rather than fixed. The vehicles are not rigid compartments but pedagogical frameworks that can coexist within and across cultural boundaries. Recognizing this diversity helps avoid simplistic classifications and better reflects the living, evolving nature of Buddhism.

Conclusion

The distinction between the doctrinal metaphor of the three vehicles and the historical development of the three major schools — Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna — provides a valuable framework for understanding the evolution and diversity of Buddhism. Each system offers different tools for spiritual progress, distinct institutional structures, and regionally shaped expressions of the Dharma. Yet none of them can fully encapsulate Buddhism as a whole.

The three vehicles — small, great, and one — emerged primarily from Mahāyāna literature as pedagogical constructs to describe varying depths and scopes of practice. They are not neutral taxonomies, but ideological narratives meant to promote certain soteriological ideals, especially the Bodhisattva path. While these metaphors offer useful insight into Buddhist doctrinal innovation, they do not necessarily correspond to how practitioners and schools historically identified themselves.

By contrast, the three schools represent real institutional and cultural histories that reflect the geographic, linguistic, and social diversity of Buddhism. Theravāda maintains the most direct link to the early Buddhist councils and canonical traditions, particularly through the preservation of the Pāli Canon and the continuation of strict monastic codes. It developed a clear emphasis on meditative insight and the ideal of the arahant, serving as a model for early Buddhist orthodoxy and discipline.

Mahāyāna, in its turn, became a crucible of philosophical innovation and devotional expansion. It produced a vast body of sūtras and scholastic texts, introduced the Bodhisattva path as a universal aspiration, and integrated ritual, cosmology, and the arts into its religious life. Its schools helped define much of East Asian Buddhism, contributing to unique religious landscapes in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

Vajrayāna built upon these foundations with a specialized esoteric methodology aimed at rapid transformation. Its integration of tantric practice, visualization, and ritual empowerment distinguished it from other Buddhist movements. By incorporating indigenous Himalayan beliefs and elaborate lineage systems, Vajrayāna created a sophisticated synthesis that preserved Mahāyāna doctrine while developing a unique spiritual infrastructure.

Each of these schools has continuously evolved, responding to local cultural conditions, political frameworks, and changing social needs. They represent not rigid containers of doctrine, but dynamic institutions capable of adapting Buddhist teachings to new contexts while maintaining continuity with earlier traditions.

Understanding the intersections and divergences between the doctrinal frameworks (vehicles) and institutional traditions (schools) helps clarify both their pedagogical intentions and historical limitations. It discourages reductive comparisons and promotes a more nuanced appreciation of how Buddhism has been shaped by philosophical vision, practical needs, and cultural exchange. Taken together, the three schools illustrate the flexibility and enduring relevance of Buddhist thought and practice across diverse times and places.

References and further readings

- Oliver Freiberger, Christoph Kleine, Buddhismus - Handbuch und kritische Einführung, 2011, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN: 9783525500040

- Rupert Gethin, The Foundations Of Buddhism, 1998, Oxford University Press, ISBN: 9780192892232

- Oliver Bottini, Das grosse O.W. Barth-Buch des Buddhismus, 2004, Ebner & Spiegel GmbH, ISBN: 9783502611264

- Richard Francis Gombrich, How Buddhism began – The conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 2006, Taylor & Francis, ISBN: 9780415371230

- Sebastian Gäb, Die Philosophie des Buddha - Eine Einführung, 2024, UTB, ISBN: 9783825262013

- Erich Frauwallner, Die Philosophie des Buddhismus, 2009, De Gruyter Akademie Forschung, ISBN: 978-3050045313

- Mark Siderits, Buddhism As Philosophy - An Introduction, 2007, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN: 9780754653691

- Richard Francis Gombrich, What the Buddha thought, 2009, Equinox Publishing (UK), ISBN: 9781845536121

- Walpola Rāhula, What the Buddha taught, 1974, Grove Press, ISBN: 9780802130310

- Jr. Buswell, Robert E., Jr. Lopez, Donald S., Juhn Ahn, J. Wayne Bass, William Chu, The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 2014, Princeton University Press, ISBN: 978-0-691-15786-3

comments